My next book – The Missing Heart – is a thriller set in two time frames – D-Day 1944, and Hastings 1066. One army lands in France, the other in Sussex. Hopefully the story is taut, and tense, and pacey with lots of action. But it’s also about something, but mainly courage, cowardice, and redemption. The problem is that as soon as you start putting such ideas on the page it tends to make for what writers call ‘the soggy middle’ – there’s a loss of direction, a feeling perhaps that the reader is being lectured, or given a sermon. This is why I’ve chosen this image above – it sums up the right way – at least for me – to freight a book with ideas, but not to overwhelm it with pious, or worse – obvious – psychological musings.

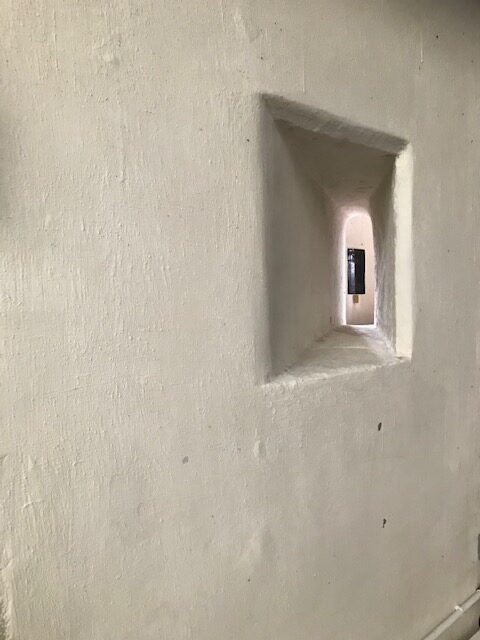

The picture shows a squint. This one is in St John’s, Barnack, in Huntingdonshire. I went wandering there because it is the site of a quarry, the stone from which built three cathedrals – Norwich, Peterborough and Ely. The church itself is a Saxon jewel – and has probably the first spire in England. But it also has a squint – or a Hagioscope, from the Latin for ‘to see’ and ‘holy’. They were splayed, narrow, tunnels cut through the cancel wall which allowed those parishioners in the side chapel to glimpse the altar, and the host, when it was elevated by the priest. The side chapels were often memorial chapels to a family, and so relatives could sit in their special place and take part in the mass with everyone else siting in the nave.

Sometime they were cut through the outside wall of the church to allow lepers, or other undesirables, to see the sacrament, and take part in the mass, but keep away from the congregation. In this case the hagioscope is called a lychnoscope – a word you don’t hear very often! But Hagioscope sounds familiar, because books about saints, which for centuries were the only books, were called hagiographies. Holy writing. But the word has become pejorative, implying something is flattering, as so many of those saintly lives were.

I like squints because they remind me to write as if I’m sitting in my memorial chapel – eyes front, telling a story, but every now and then allowing the reader to see – out of the corner of their eyes – a bigger story, a theme, an idea. At the moment I’m trying to write several scenes in The Missing Heart which involve the famous – and the infamous. For example, I wanted to write about a meeting between Winston Churchill and General De Gaulle, the leader of the Free French. My big theme – courage – is integral to the scene but I don’t want to bludgeon the reader with it. I need them to see it – sideways – but while being diverted by other things, De Gaulle’s penchant for cheese pastries and Gitanes, Churchill’s obsession with lying in the bath (the train has one) or playing Patience – or Solitaire, as De Gaulle points out. (A French invention)

We also need a setting which diverts us from looking down that squint – at history, and great events. So, instead of putting them in a room in Downing Street, or De Gaulle’s suite in the Carlton Hotel in Mayfair, I made up a meeting that never happened – in Churchill’s special train, in a siding outside Portsmouth, a few days after D-Day. Both men display courage – of a type, psychological perhaps, rather than physical or emotional. But the scene is played out for comic effect, with Anthony Eden, the Foreign Secretary an appalled guest for dinner, watching the two men try to tear each other apart: De Gaulle must go to France, but Churchill can not let him proclaim a new republic. The Amercians want to set up a military council first, and Rooseveldt’s wishes trump all else in London. In the end the two men, exhausted after ritual insults and abuse, opt for champagne and cards. De Gaulle, softening, reveals that he often sits beside Anne, his severely disabled daughter, at the card table when they have guests at home, and plays the cards for her. It’s an insight, a view of another type of courage. When De Gaulle died he stipulated that he should be buried beside her. The reader should be invested in this scene, should feel they are there in the old dining car, the sound of Ack Ack fire heard over the distant Channel. But the big issues should just impinge, glimsped through the literary squint.