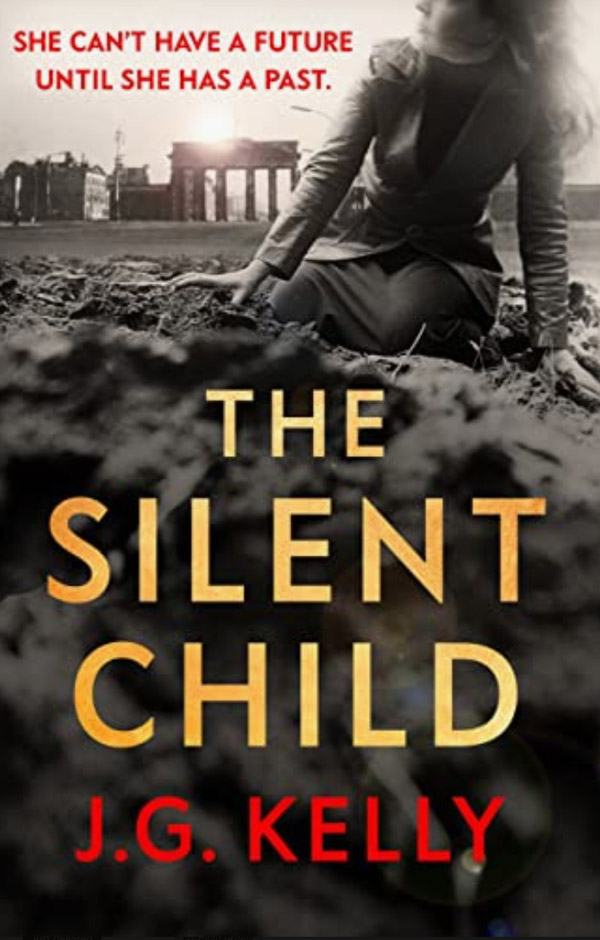

You never know where you might find a good story to tell, but history is a wonderful place to start. The Silent Child, my latest book, is set firmly within two historical timeframes: Poland in the Second World War, and a Berlin in 1961 divided into zones by the Allied Powers of the Soviet Union, Britain, France and the United States.

Where did the story come from? Inspiration – for me – is not about finding an old tale to retell, but of finding the shape of a story in the past which can inspire fiction. I’m always looking for these story-shapes. They’re like templates which you can use to make your own tale. For a novel to really have life it needs to tell narrative for the first time – this is the heart of a story, without which it would merely be a jigsaw of old pieces rearranged.

In 2010 I was invited to a wedding in Krakow, in southern Poland. Tourists flock there now, to enjoy an unspoilt medieval city. The past lives alongside the present.

It is a place rich in stories. My favourite is the hejnal mariacki – St Mary’s Trumpet Call, which appears in the historical record for the first time in 1392. A trumpeter sounds a bugle call from the highest tower of St Mary’s Basilica, which stands on the city’s great square.

The call is interrupted – as if the musician has suddenly been struck down. He makes the call four times, never completing it, but facing in a different direction every time. This happens every hour, and is broadcast on radio live at noon across Poland, and the wider world. It may be that it used to herald the closing and opening of the city’s four gates, and that when the trumpeter stops the call was taken up by each of the gates in turn to signal that they’d heard.

There is another legend that during the Mongol invasion of Poland a sentry on the tower sounded the trumpet alarm as the enemy approached – but he was shot in the throat with an arrow before he could finish the warning.

The shape of this story is appealing – a signal which requires a coded answer, the killing of the lookout before the code is complete. It’s certainly the start of a story – one which could easily be transferred from Poland to – perhaps – the D-Day landings, when Allied troops had to fight through the fields and hedges and sunken lanes of Normandy, and were given metal ‘clickers’ with which to seek out friendly paratroopers in the dark. It’s a story which will appear (heavily disguised) in one of the books to follow The Silent Child.

Krakow also provided the spark which led to The Silent Child itself. Most of the guests for the wedding I attended with my daughter arrived in the city three days early, and while one group took the children to see the Wawel Dragon of Krakow in his cave under the castle the rest went to Auschwitz.

The coach journey provided an opportunity for visitors to watch a film about the camp and its liberation. By the time we arrived everyone was braced for the worst. Standing in the gas chamber at Auschwitz 1 we were welcomed by a guide. It was a silent audience.

The past is a suffocating presence. It was a remarkable few hours – especially after we took the short journey along the road to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the main camp, and a symbol now recognised worldwide of the Holocaust.

Here stand the remains of crematoria used to dispose of the bodies of more than a million jews. But the story I took away that day – or at least the one that took root – was a surprise.

In October 1944, when it was clear the Germans were quitting the camp, and would murder the Jews still alive before the Allies arrived, there was an uprising at one of the crematoria. The jews – mainly from Hungary and Greece – set fire to the building and killed the SS guards. Others – thinking a general uprising had begun – managed to reach a nearby village.

In the end most were tracked down – over 450 were killed. This was a story I did not expect – and which flew in the face of the cliché that the jews had failed to resist their fate.

Was it a one off? Not at all: at Trebinka in 1943 there was a well organised uprising, the jews took possession of the armoury and broke out, although most were rounded up later in the forests and shot. At Sobibor 300 escaped – at least initially. Outbreaks at other camps were even better organised, and allowed the inmates to join up with Polish partisans.

All great stories inspire questions: who survived the revolts and why? How did they get hold of weapons ? Who led them? What happened to the children? There was a shape of a story here: a child might have survived, but what would they remember? That visit led me to a girl called Hanna – who never existed but is real to me. She is The Silent Child.